Understanding Trigger Point Theory

Modern Science Behind Muscle Pain & Trigger Point Dry Needling

Note: Acupuncture refers to any intervention that punctures the skin with an acupuncture needle; this includes hundreds of styles and techniques. Dry needling is a needling style that uses acupuncture needles, and may be practiced by licensed acupuncturists, medical doctors, or physical therapists, or other providers depending on local laws.

Chronic muscle pain affects over 1.7 billion people globally and is one of the leading causes of disability and lost productivity. When traditional imaging and orthopedic exams fail to identify the source of pain, clinicians often turn to trigger point theory, the idea that small, irritable knots in muscle tissue may drive both local and referred pain.

In 2024, researchers published a new review in Frontiers in Medicine that updated and refined trigger point theory. It classifies muscle pain into three predictable patterns:

Muscle Belly Pain

Origin-Insertion Pain

Referred Pain

This reorganization promises faster diagnosis, clearer patient education, and more targeted interventions such as dry needling and exercise therapy. The expanded post below unpacks each section of the study in depth and translates the findings into day‑to‑day clinical practice.

👉 If you're new to the diversity of needling styles, check out our Ultimate List of Acupuncture Styles.

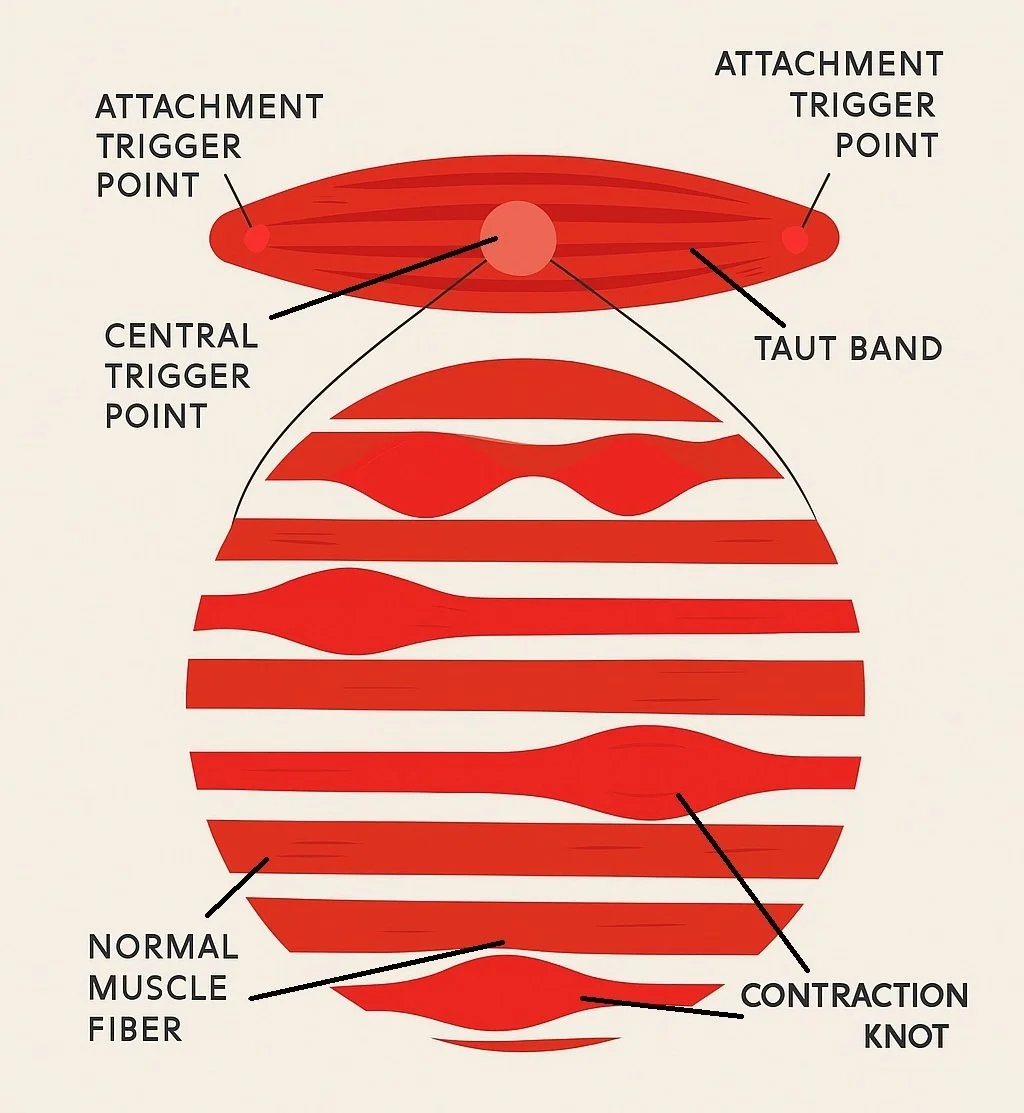

A modern anatomical diagram of a taut muscle band with labeled central and attachment trigger points, contraction knots, and normal muscle fibers, based on the 2024 review of trigger point theory.

Key Points

Trigger points are irritable spots in muscle that disrupt local biochemistry and nerve signaling.

Three key patterns: muscle belly, origin-insertion, and referred pain explain most chronic muscle pain.

Dry needling may reduce pain by restoring blood flow, disrupting taut bands, and modulating nerve responses.

New trigger point maps integrate biomechanics and peripheral nerve patterns.

Effective care requires combining needling with movement assessment, exercise, and education.

What Are Trigger Points?

Trigger points are hyperirritable nodules in skeletal muscle fibers that form taut bands, often after injury or chronic overload. These spots are typically painful on compression, reproduce a familiar pain pattern, and often elicit twitch responses on palpation or needling.

Biochemical Characteristics

Research shows that trigger point tissue has low oxygen, increased acidity, elevated inflammatory mediators, and spontaneous electrical activity. This creates a self-sustaining cycle of tension and pain.

| Marker / Phenomenon | Trigger‑Point Zone (vs. Healthy) | Key Clinical Implication | Simple Summary |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxygen Tension | ↓ up to 50 % | Ischaemic pain & early fatigue | Less blood → muscle “starves” for oxygen. |

| pH Level | 6.6 – 6.8 (acidic) | Acidaemia sensitises nociceptors | Knotted area turns acidic—nerves get irritable. |

| IL‑6 / TNF‑α / SP / CGRP | 2 – 7 × baseline | Neurogenic inflammation | Chemical “soup” drives pain & swelling. |

| Spontaneous Electrical Activity | Persistent end‑plate noise | Twitch response on needle insertion | Muscle fibers keep firing even at rest. |

These biochemical signatures reinforce the need for mechanical disruption plus vascular reperfusion, which is exactly what dry‑needling techniques and post‑treatment aerobic exercise provide.

The Three Muscle Pain Patterns

Trigger point-related pain doesn’t always stay local. It follows distinct patterns based on the structure and function of the affected muscle.

In their 2024 review, Zhai et al. propose a clinically useful classification that divides muscle pain into three core types. Understanding whether a patient’s pain stems from the muscle belly, its tendinous attachment, or a distant referred site helps guide accurate diagnosis and targeted treatment strategies like dry needling, manual therapy, and corrective exercise.

1. Muscle Belly Pain

Pain located in the midsection (belly) of the muscle, usually caused by overuse or stretching. It responds well to biomechanics-focused treatment.

2. Origin-Insertion Pain

This pain arises at tendon attachment points and is commonly found in conditions like patellar tendonitis, tennis elbow, or plantar fasciitis.

3. Referred Pain

Pain experienced away from the trigger point, following nerve pathways. It may be due to nerve trunk irritation, shared nerve roots, or atypical “special” referral zones.

| Pain Type | Muscles Affected | % of Muscles |

|---|---|---|

| Muscle Belly Pain | 76 / 89 | 85.4 % |

| Origin–Insertion Pain | 72 / 89 | 80.9 % |

| Referred Pain | 31 / 89 | 34.8 % |

Neuromuscular Mechanisms & Central Sensitization

Trigger points start with a localized “energy crisis” in the muscle: poor blood flow, low oxygen, and acidic build-up that irritate nerves and sustain contraction. Over time, this can lead to central sensitization, where the brain and spinal cord overreact to even mild signals, amplifying pain beyond the original site.

Diagnosis & Clinical Evaluation

Palpation: Feel for taut bands and reproduce familiar pain

Biomechanical screening: Evaluate posture, movement patterns, joint alignment

Movement assessment: Identify aggravating patterns

Rule out red flags: Fracture, infection, systemic disease

Study Overview

Aim – To integrate biomechanics, neuromuscular physiology, and trigger‑point mapping into a unified clinical model.

Methodology (key points):

Reviewed 255 TrP maps from the second edition vs. 89 muscle patterns in the 2019 third edition.

Re‑classified pain into three categories based on anatomical site, load mechanism, and neural referral.

Tabulated the prevalence of each pattern across six body regions.

| Body Region | Muscles Analysed |

Muscle Belly Pain | Origin‑Insertion Pain | Referred Pain* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Head, Face & Neck | 11 | 8 | 9 | 8 |

| Upper Back & Shoulder | 13 | 9 | 11 | 4 |

| Forearm, Wrist & Hand | 18 | 14 | 8 | 6 |

| Trunk & Pelvis | 15 | 13 | 14 | 5 |

| Hip, Thigh & Knee | 16 | 16 | 15 | 4 |

| Calf, Ankle & Foot | 16 | 16 | 15 | 4 |

| Total (89) | 76 (85.4%) | 72 (80.9%) | 31 (34.8%) | |

| *Referred pain includes same‑root radicular and peripheral‑nerve referrals. | ||||

Pathophysiology of Trigger Points—Beyond “Knots”

The Energy‑Crisis Model

Repetitive overload or sudden trauma → sustained sarcomere contraction.

Local blood flow drops, oxygen tension falls, pH slides to < 6.8, and metabolites (bradykinin, SP, CGRP, IL‑6) accumulate.

Nociceptors and chemoreceptors fire incessantly, producing spontaneous electrical activity (“end‑plate noise”).

The 2024 paper highlights that up‑regulated acetylcholine spill‑over at the motor‑end plate perpetuates contraction—linking electrophysiology with clinical palpation findings.

Peripheral–Central Continuum

Untreated TrPs bombard the dorsal horn, lowering inhibitory thresholds and fostering central sensitisation. Patients then develop allodynia (“everything hurts”) and multi‑site pain even after the original tissue heals. This explains why local needling often yields immediate relief, but long‑term success requires CNS down‑regulation through education, graded exposure, and aerobic exercise.

Muscle Belly Pain: The Contractile Core

Definition – Pain localized to the mid‑portion of a muscle belly, usually triggered by overstretch, eccentric overload, or prolonged static posture.

Key insights from the study:

85 % of mapped muscles displayed a belly pain component.

Common clinical examples include rhomboid pain from desk‑bound scapular protraction and quadratus lumborum pain after contralateral side‑flexion sports.

Agonist–antagonist imbalance, not just local injury, sustains tightness—e.g., tight pectoralis minor → overstretched rhomboids → medial scapular ache.

Clinical Pearl – Assessment Flow

Palpate the taut band; reproduce the patient’s “familiar” pain.

Test antagonist length/strength (e.g., pectoralis minor for rhomboid pain).

Evaluate regional joint control (scapulothoracic rhythm, hip rotation, etc.).

Treat the belly TrP, then re‑train opposing musculature to maintain change.

Origin‑Insertion Pain: The Tendon Junction

Definition – Pain at musculotendinous or osteotendinous attachments, linked to high tensile load and micro‑tears.

Study contributions:

81 % of muscles exhibited origin‑insertion pain; prevalence highest in quadriceps–patellar complex and forearm extensors.

Chronic repetitive traction (e.g., adolescent tibial tuberosity in Osgood–Schlatter) was a recurring theme.

Imaging often shows cortical thickening, enthesophytes, or bone marrow oedema—organic proof that TrPs and tendinopathy intersect.

Practical Example

A distance runner with infrapatellar pain:

• Needling the distal quadriceps relieves the immediate nociceptive drive.

• Shockwave or isometric loading addresses tendon adaptation.

• Gait retraining corrects over‑stride that perpetuates the traction.

Referred Pain: When Distance Misleads

Zhai et al. subdivide referral into three mechanisms:

Peripheral‑Nerve Referred Pain – A TrP irritates a nerve trunk traversing the muscle (e.g., scalene compression of long thoracic nerve → medial scapular & thumb pain).

Same‑Root Radicular Pain – Persistent TrP bombardment alters axoplasmic flow, sensitizing the shared dorsal‑root ganglion (e.g., gluteus minimus trigger → lateral leg ache mimicking L5 radiculopathy).

Special Referred Pain – Atypical patterns lacking clear neuroanatomical rationale, such as diaphragm TrP causing supra‑clavicular pain.

Why This Matters Clinically

Misattribution leads to unnecessary spinal imaging or nerve‑root injections.

Treating the true myofascial source can extinguish distal symptoms (e.g., needling iliopsoas for “groin” neuralgia).

Diagnostic & Functional Assessment – Step‑By‑Step

Subjective map – Have patients color painful zones; compare to three pattern templates.

Palpation & twitch sign – Confirms TrP presence.

Range‑of‑motion & strength tests – Identify biomechanical drivers (e.g., hip internal‑rotation deficit).

Dynamic movement screen – Squat, gait, overhead reach to reveal faulty loading.

Red‑flag screen – Infection, fracture, systemic disease, visceral referral.

Using the study’s framework, novice therapists can shorten diagnostic time yet preserve safety.

Evidence‑Based Treatment Options (Expanded)

| Intervention | Primary Physiologic Target | Dosing Principles | Best‑Match Pain Patterns |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dry Needling | Disrupt taut band; normalise pH & cytokines; activate descending inhibition | 6‑12 quick passes until twitch; 1‑2×/week | All three |

| Electroacupuncture | Muscle pumping; endorphin release | 2‑10 Hz, 15‑20 min | Chronic belly / radicular referral |

| Ischaemic Compression | Reactive hyperaemia; gate control | 60‑90 sec holds × 3 | Local belly pain |

| Shockwave Therapy | Mechanotransduction; neovascularisation | 2,000‑3,000 pulses weekly × 3‑5 | Origin‑insertion pain |

| Low‑Load Isometrics | Tendon collagen turnover; cortical inhibition | 45 s holds × 5 @ 70 % MVC | Origin‑insertion & chronic referral |

| Graded Aerobic Exercise | Central inhibition; improved capillarisation | 20 min Zone‑2, 3×/week | Central sensitisation overlap |

Meta‑analysis cited in the paper confirms dry needling reduces pain and improves function at short‑to‑medium follow‑up in neck, shoulder, knee, and plantar fasciitis cohorts.

Limitations & Research Gaps

Subjective mapping – Referred‑pain diagrams rely on patient description; inter‑tester reliability remains moderate.

Biomechanical blind spots – Charts rarely integrate kinetic‑chain contributors (e.g., hip instability in iliotibial‑band pain).

Need for objective biomarkers – Emerging ultrasound elastography and microdialysis may eventually confirm TrP physiology non‑invasively.

Under‑representation of psychosocial factors – Chronic pain is biopsychosocial; TrPs are one piece of a larger puzzle.

Zhai et al. call for multicenter trials combining needling, biomechanics, and psychology to capture the full complexity of chronic pain.

A Multidisciplinary Care Pathway

Acupuncturist / PT – Identify and needle primary TrPs; teach self‑release.

Strength & Conditioning – Load progression (isometrics → eccentrics → sports‑specific plyometrics).

Pain Psychologist – Address catastrophising, fear‑avoidance.

Physiatrist / Sports MD – Imaging or pharmacologic adjunct when red flags appear.

Patient Education – Sleep, recovery, hydration, stress.

Practical Takeaways for Clinicians & Patients

Map pain to belly, attachment, or referral first: it dictates needle placement and exercise selection.

Peripheral‑nerve referral often resolves when the intramuscular segment is released.

Attachment pain without biomechanical correction → high recurrence risk.

Combine local therapies (needling, compression) with global load management (strength, sleep, stress).

Monitor for signs of central sensitization: disproportionate pain, mood change, sleep disturbance.

Re‑assess every 2–3 visits; refine the hypothesis, don’t chase symptoms.

| Key Question | Simple Answer | Practical Clinical Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Where do most trigger points hurt? | In the middle of the muscle belly. | Start palpation and needling in the thickest part of the muscle first. |

| Why do tendon attachments ache? | Repeated pulling irritates the tendon–bone junction. | Combine dry needling with load‑management exercises for long‑term relief. |

| Can a hip muscle cause leg pain? | Yes—tight hip muscles can refer pain down the leg through shared nerve roots. | Treat proximal muscles before ordering unnecessary spine imaging. |

| What keeps a trigger point “on”? | Low oxygen, acidic pH, and chemical buildup in the muscle knot. | Techniques that restore blood flow (needling, movement) help turn it “off.” |

| Why does pain sometimes spread? | The spinal cord can become sensitised after constant nociceptive input. | Add aerobic exercise and education to calm the nervous system, not just the muscle. |

| How fast can dry needling work? | Many patients feel relief immediately or within 1–2 sessions. | Use quick in‑and‑out passes until a local twitch response is seen. |

| Do charts fit every patient? | No—pain maps are guides, not guarantees. | Always confirm by reproducing the patient’s “familiar” pain during palpation. |

| What prevents recurrence? | Correcting posture, strength, and daily load—not just treating the knot. | Finish each session with targeted exercises and self‑care instructions. |

Conclusion

Trigger‑point theory has matured from isolated “knots” rhetoric to a systems‑based model connecting local biochemistry, neural circuitry, and whole‑body mechanics. The 2024 re‑classification into belly, origin‑insertion, and referred pain offers a pragmatic roadmap for faster diagnosis and more precise care.

Whether you’re an athlete nursing Achilles pain or an office worker battling neck tension, integrating dry needling with movement correction and education can shorten recovery and reduce recurrence.

Ready to Try Dry Needling?

Whether you’re struggling with muscle pain, tension headaches, or limited mobility, dry needling may help restore muscle function and reduce pain - quickly and safely.

📍 Conveniently located in New York City

🧠 Experts in trigger point therapy, acupuncture, and dry needling

Book your appointment today with the experts at Morningside Acupuncture, the top-rated acupuncture and dry needling clinic in New York City.

Let us help you move better, feel stronger, and live pain-free.

Related Questions:

-

A trigger point is a hyper‑irritable knot within a taut band of skeletal‑muscle fibres. It can generate local tenderness and predictable referred‑pain patterns. Biochemical analysis shows low oxygen, acidic pH and an inflammatory “chemical soup,” which together may sensitize nearby nerves and perpetuate pain.

-

Trigger point pain typically arises in the muscle belly or at its tendon attachment and may reproduce familiar, sometimes traveling, pain when pressed. Joint pain is usually deep and mechanical (e.g., clicking, locking), while tendon pain often peaks during loading (running, jumping). A comprehensive exam can confirm which structure is the main pain generator.

-

Research suggests dry needling can produce an immediate local twitch response that may reduce muscle tension and normalise pH. Many patients report partial relief after 1–2 sessions; lasting change usually requires follow‑up exercise and movement retraining.

-

Not exactly. Acupuncture refers to any intervention that pierces the skin with an acupuncture needle; dry needling is one needling style that focuses on myofascial trigger points. Depending on local laws, it may be performed by licensed acupuncturists, medical doctors or physical therapists.

See the Ultimate List of Acupuncture Styles for details.

-

Zhai et al. (2024) describe three referral mechanisms: peripheral‑nerve irritation, shared nerve‑root sensitisation and special (atypical) referral. In each case, the nervous system carries the signal away from the muscle, so pain may appear in a seemingly unrelated area—e.g., gluteus minimus trigger points may cause lateral‑leg discomfort.

-

The 2024 review found 85 % of muscles show muscle‑belly pain, 81 % origin‑insertion pain, and 35 % referred pain. Most patients actually present with a mix, which explains why needling both the belly and the tendon attachment often provides best results.

-

Evidence supports combining dry needling with low‑load isometrics, progressive strength training, posture correction and patient education. Modalities such as shockwave therapy or electroacupuncture may further improve circulation and pain modulation in chronic cases.

-

When performed by a properly trained, licensed professional, adverse events are rare and usually minor (temporary soreness, light bruising). All needles are single‑use and sterile. Contraindications include active infection at the insertion site, uncontrolled anticoagulation and certain systemic illnesses—these will be screened at your visit.

Sources:

Zhai, T., Jiang, F., Chen, Y., Wang, J., & Feng, W. (2024). Advancing musculoskeletal diagnosis and therapy: A comprehensive review of trigger point theory and muscle pain patterns. Frontiers in Medicine, 11, 1433070. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2024.1433070/full

Disclaimer: This web site is intended for educational and informational purposes only. Reading this website does not constitute providing medical advice or any professional services. This information should not be used for diagnosing or treating any health issue or disease. Those seeking medical advice should consult with a licensed physician. Seek the advice of a medical doctor or other qualified health professional for any medical condition. If you think you have a medical emergency, call 911 or go to the emergency room. No acupuncturist-patient relationship is created by reading this website or using the information. Morningside Acupuncture PLLC and its employees and contributors do not make any express or implied representations with respect to the information on this site or its use.