Trigger Points

A Guide to Understanding and Managing Myofascial Trigger Points

Introduction

Myofascial trigger points (MTrPs) are hyperirritable spots in skeletal muscle that play a central role in chronic musculoskeletal pain. This guide explains what trigger points are, their historical evolution, the mechanisms behind their development, and how they are diagnosed and treated.

What Are Trigger Points?

Trigger points are localized, tender nodules found within taut bands of muscle fibers. They are classified as:

Active Trigger Points: These produce spontaneous pain and mimic the patient’s familiar pain complaint when pressed.

Latent Trigger Points: These are not spontaneously painful but become tender upon palpation.

Recognizing these trigger points is essential for diagnosing myofascial pain syndrome (MPS) and planning effective treatment.

Historical Perspective

Early clinicians, from de Baillou to Steindler, observed firm, painful nodules in muscle tissue, though their significance was not fully understood. It wasn’t until the groundbreaking work of Travell and Simons in the 1950s that the concept of trigger points was refined and linked directly to musculoskeletal pain (Travell & Simons, 1983). Their observations paved the way for modern techniques such as dry needling and manual therapy.

Clinical Characteristics of Trigger Points

The hallmark of trigger points is the local twitch response—a brief, involuntary contraction of muscle fibers when the trigger point is stimulated. Additional clinical features include:

Palpable Nodules: Detectable as firm, tender spots during muscle palpation.

Referred Pain: Pain that radiates from the trigger point to other areas, following specific patterns.

Muscle Stiffness and Restricted Range of Motion: Often accompanying trigger point activity.

Pathophysiology and Mechanisms

Trigger points are believed to arise from a combination of factors:

Abnormal Neuromuscular Activity: Excessive release of acetylcholine at the motor endplate may lead to sustained contraction of sarcomeres, creating a trigger point.

Biochemical Changes: Studies using microdialysis have shown that active trigger points have elevated levels of inflammatory mediators and other nociceptive substances (Shah & Gilliams, 2008).

Sensitization: Both peripheral and central sensitization can occur, where local nerve endings become more responsive and pain signals are amplified by the central nervous system.

These mechanisms help explain why trigger points cause both local pain and pain that is referred to distant areas.

Diagnostic Criteria and Techniques

Clinical Assessment

Diagnosing trigger points is primarily a clinical process that involves:

Patient History: A thorough discussion about the nature, location, and referral pattern of pain.

Physical Examination: Careful palpation of muscles to detect tender nodules and eliciting the local twitch response.

Objective Measures: Tools such as pressure algometry can help quantify the pain threshold at trigger points, while advanced imaging techniques (e.g., ultrasound) are sometimes used to evaluate muscle tissue structure.

Summary Table: Active vs. Latent Trigger Points

| Characteristic | Active Trigger Points | Latent Trigger Points |

|---|---|---|

| Pain | Spontaneously painful; pain is present even at rest. | Not painful unless stimulated by pressure. |

| Response to Palpation | Elicits a strong local twitch response and reproduces familiar pain. | May produce a twitch response but only causes pain on palpation. |

| Impact on Function | Often associated with significant muscle stiffness and limited range of motion. | Can cause subtle dysfunction, typically less severe than active points. |

| Clinical Significance | Directly linked to patient’s reported pain and disability. | May indicate early muscle dysfunction and potential for future pain. |

Diagnostic Tools

Clinicians may use:

Pain Scales: Such as the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) to quantify pain intensity.

Pressure Algometry: To measure pain pressure thresholds at suspected trigger points.

Imaging Techniques: Although not routinely used, ultrasound or MRI can provide additional insight in complex cases.

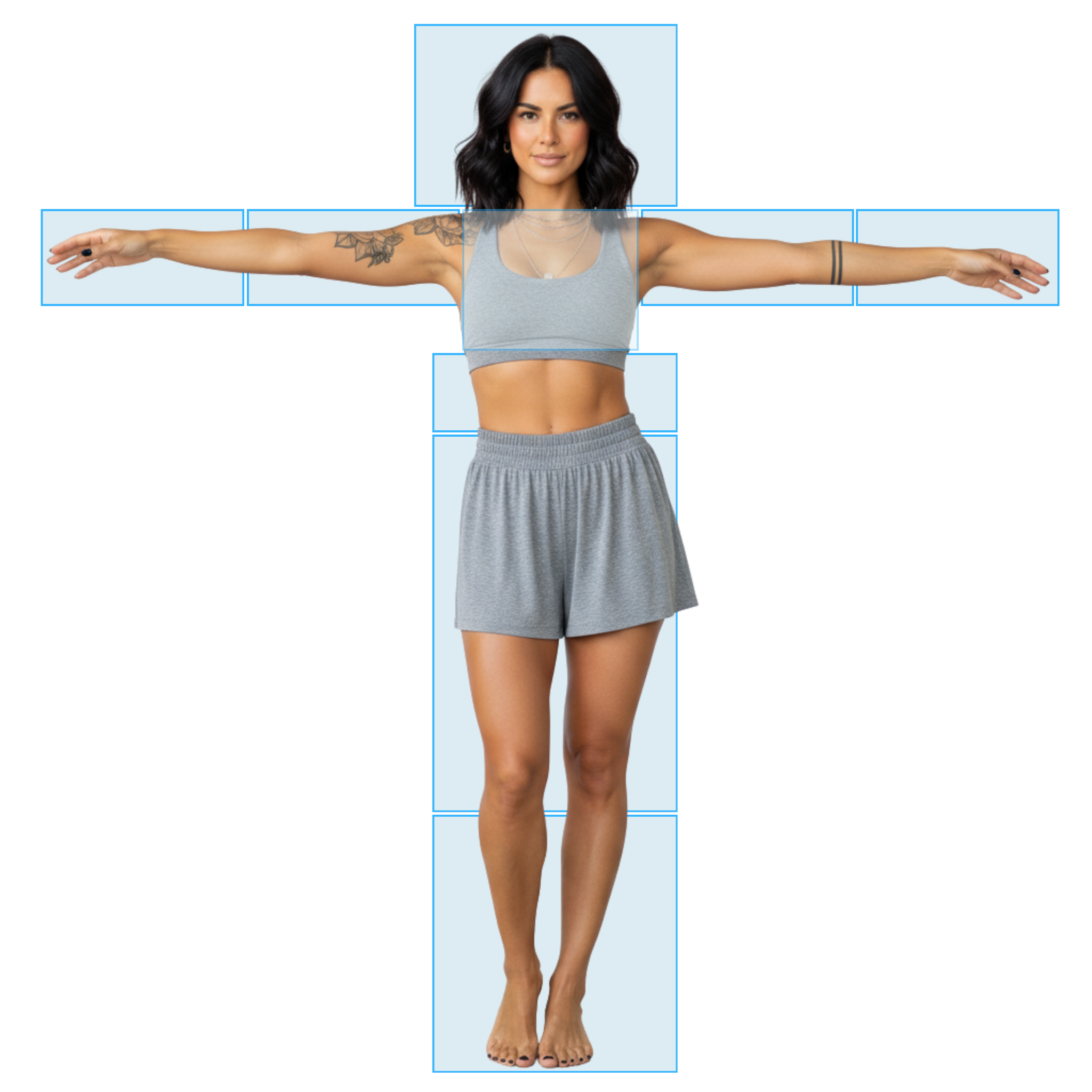

Try Our Interactive Tool

Trigger Points Often Explain

“Mystery Pain”

Our Trigger Point Pain Finder lets you click on the area where you feel discomfort, explore symptom patterns, and better understand which muscles may benefit from dry needling or acupuncture.

Treatment Options for Trigger Points

Manual and Needling Therapies

The treatment of trigger points focuses on deactivating these hyperirritable spots:

Dry Needling: Involves inserting a fine needle directly into the trigger point to provoke a local twitch response, thereby releasing tension and reducing pain. Research supports its effectiveness for short-term pain relief (Chys et al., 2023).

Manual Therapy and Massage: Techniques that help relax muscle tissue and release trigger points.

Injections: In some cases, local anesthetic injections are used, although dry needling avoids the risks associated with pharmacological agents.

Integrative Approaches

For optimal outcomes, trigger point treatments are often combined with other interventions, such as stretching, exercise, and postural corrections, to address underlying biomechanical issues.

➡️ Learn More: Trigger Points Treatment

➡️ Learn More: Acupuncture Points and Myofascial Trigger Points

Trigger Point Index

Explore our Trigger Point Index for in-depth insights and useful information about how trigger points affect specific muscles.

➡️ Learn More: Trigger Point Index

Research and Evidence

Recent research has helped clarify the role of trigger points in musculoskeletal pain. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses indicate that interventions targeting trigger points—such as dry needling—can effectively reduce pain and improve function in the short term (Wang et al., 2024). However, long-term outcomes and standardized diagnostic criteria remain areas of ongoing study.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: What exactly is a trigger point?

A trigger point is a small, sensitive area within a muscle that is tender to touch and may produce pain in other parts of the body when pressed. These are central to diagnosing myofascial pain syndrome (Travell & Simons, 1983).

Q: How do I know if my pain is caused by a trigger point?

Trigger points are often identified during a clinical exam. A key sign is a local twitch response when the area is palpated. If you experience a sudden contraction and familiar pain upon pressure, it may be a trigger point.

Q: Can trigger points exist without causing pain?

Yes. Latent trigger points do not cause pain until they are pressed, whereas active trigger points cause spontaneous pain even without pressure.

Q: What treatments are available for trigger points?

Common treatments include dry needling, manual therapy, massage, and sometimes local anesthetic injections. The choice of treatment depends on the severity and location of the trigger point.

Q: How do trigger points lead to referred pain?

Trigger points can send pain signals along nerve pathways, causing pain to be felt in areas away from the actual trigger point. This is why, for example, a trigger point in the neck may cause headache-like symptoms.

Q: Are there any imaging or biochemical tests for trigger points?

Currently, the diagnosis of trigger points is mostly clinical. However, techniques such as pressure algometry, ultrasound imaging, and microdialysis (in research settings) can provide additional objective information.

Q: Are there risks associated with treating trigger points?

When performed by a trained professional, treatments like dry needling are generally safe. Mild side effects such as temporary soreness, bleeding, or bruising may occur, but serious complications are rare (Boyce et al., 2020).

➡️ Learn More: Trigger Points FAQ

Conclusion

Myofascial trigger points are a key component of chronic musculoskeletal pain. Understanding their history, underlying mechanisms, and clinical presentation is essential for effective diagnosis and treatment. By targeting trigger points with interventions such as dry needling and manual therapy, clinicians can help relieve pain and restore function.

💡Additional Trigger Point Pages

Keep exploring the world of Trigger Points with the following resources. From in-depth research and cutting-edge techniques to practical FAQs and condition-specific insights, our curated guides make it easy to find answers. Start exploring today.

Sources:

Boyce, D., Wempe, H., Campbell, C., Fuehne, S., Zylstra, E., Smith, G., Wingard, C., & Jones, R. (2020). Adverse events associated with therapeutic dry needling. The International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy, 15(1), 103–104. https://doi.org/10.26603/ijspt20200103

Chys, M., De Meulemeester, K., De Greef, I., Murillo, C., Kindt, W., Kouzouz, Y., Lescroart, B., & Cagnie, B. (2023). Clinical effectiveness of dry needling in patients with musculoskeletal pain—An umbrella review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(3), 1205. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12031205

Dommerholt, J. (2019). Needling: is there a point? [Editorial]. Journal of Manual & Manipulative Therapy. https://doi.org/10.1080/10669817.2019.1620049

Shah, J. P., & Gilliams, E. A. (2008). Uncovering the biochemical milieu of myofascial trigger points using in vivo microdialysis: An application of muscle pain concepts to myofascial pain syndrome. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, 12, 371–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbmt.2008.06.006

Travell, J. G., & Simons, D. G. (1983). Myofascial pain and dysfunction: The trigger point manual (2nd ed.). Williams & Wilkins.

Wang, M., Zhao, T., Liu, J., & Luo, S. (2024). Global trends and performance of dry needling from 2004 to 2024: A bibliometric analysis. Frontiers in Neurology, 15, Article 1465983. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2024.1465983