Dry Needling for Knee Pain

Dry needling for Knee Pain

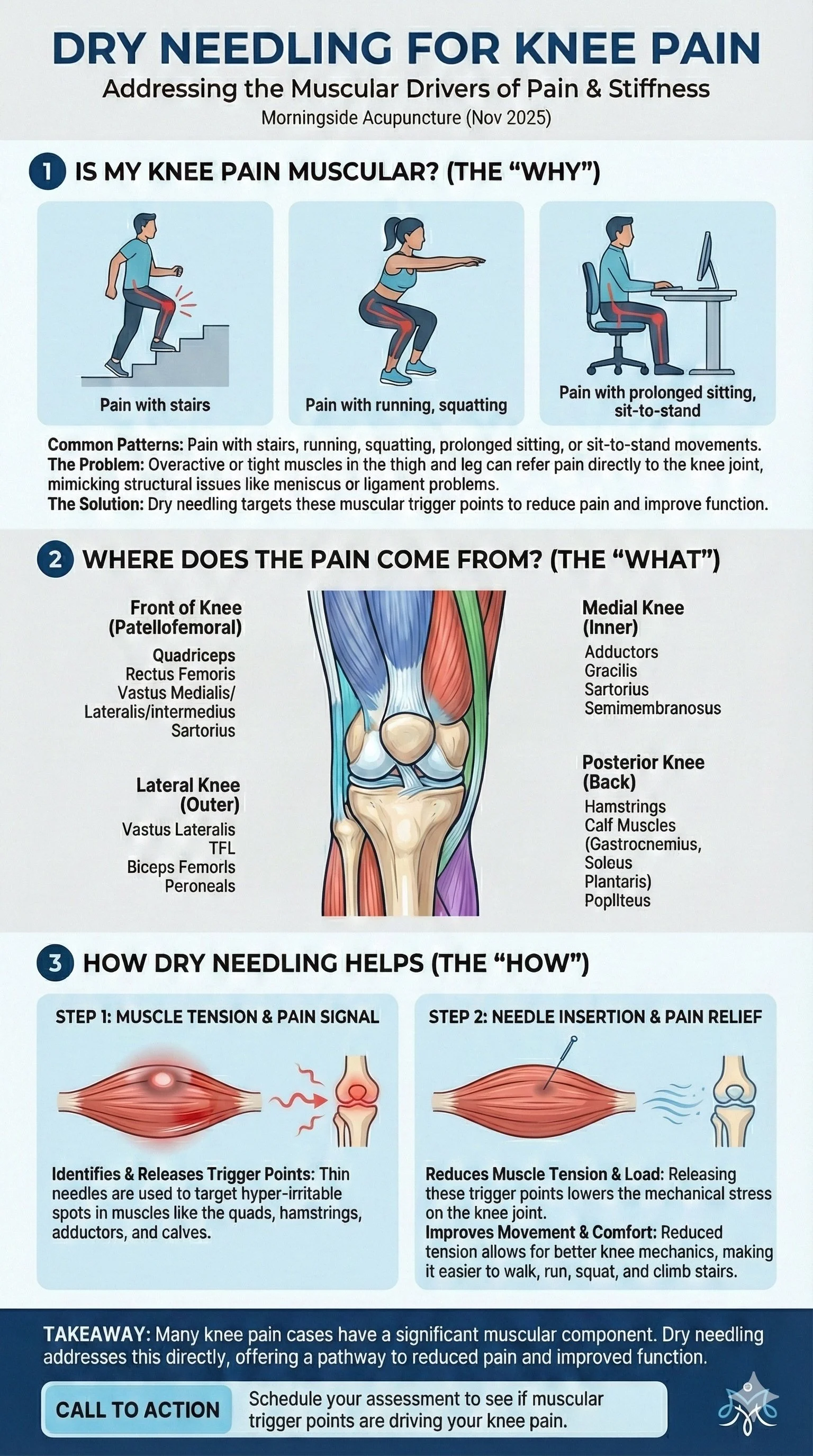

Climbing stairs sparks a sharp pull at the front of the knee; sitting through a meeting creates a dull ache along the inner joint line; finishing a run leaves the outside of the knee feeling tight and irritated. These patterns are common across many types of non-traumatic knee pain. While knee pain can come from multiple sources, a large portion of cases include a muscle-driven component: overactive quadriceps, tight hamstrings, irritated adductors, or stiff calf musculature that increases mechanical load on the knee.

Dry needling for knee pain addresses these muscular contributors directly. Many muscles above and below the knee refer pain into the joint or surrounding structures. When the exam reveals tenderness in the quadriceps, adductors, hamstrings, TFL, or calf complex, reducing trigger-point irritability may decrease nociceptive input and improve comfort during loading.

For a plain-language overview of what to expect, see the Dry Needling Guide and the Trigger Points Guide.

Key Points

Most suitable cases: knee pain with muscular cues—stairs, running, squatting, sitting-to-standing, hills, or prolonged sitting.

Primary effect: reduction of trigger-point activity in quadriceps, hamstrings, adductors, TFL, calf, and ankle stabilizers that frequently refer pain to the knee.

Muscle coverage: rectus femoris, vastus medialis/lateralis/intermedius, biceps femoris, semitendinosus, semimembranosus, adductor longus/brevis, gracilis, sartorius, TFL, gastrocnemius, soleus, plantaris, tibialis anterior/posterior, peroneus longus/brevis.

Timeline: many individuals notice a shift within 1–3 sessions; a short series of 4–6 visits is common. Long-standing patterns may require 10+ visits.

Practical trial: typically 3–5 sessions.

Session pacing: early sessions are conservative, with progression based on response.

Knee Pain: Brief Condition Overview

Knee pain arises from many sources: patellofemoral overload, tendinopathy, joint irritation, postural stress, and movement-pattern dysfunction. Yet a significant portion of knee pain cases involve muscles that refer pain directly to the knee, producing sensations that can feel deeper or more structural than they really are.

Signs & symptoms (common features):

Pain with stairs, running, squatting, or prolonged sitting

Aching at the front, inside, outside, or back of the knee

Tightness in the quadriceps, lateral thigh, hamstrings, or calf

Clicking or discomfort with sit-to-stand or bending

Pain that returns after training spikes or long inactive periods

Typical treatment options include:

Modified activity and gradual reloading

Strengthening of quadriceps, hamstrings, glute med, and calf

Movement-pattern refinement during running, squatting, and walking

Dry needling and manual therapy to reduce muscle-driven load

Footwear and training-volume adjustments

Sleep regularity, warm-ups, and pacing strategies

How Muscle Pain Can Mimic Orthopedic Knee Conditions

Many muscles that refer pain to the knee can create symptoms nearly identical to structural knee problems. It’s common for muscle-driven knee pain to be mistaken for:

Meniscus irritation

Patellofemoral syndrome

Pes anserine bursitis

IT band–related pain

Ligament sprains

Early arthritic changes

Baker’s cyst

Posterior capsule strain

Because referral patterns from the quadriceps, hamstrings, adductors, calf complex, and lateral stabilizers overlap with these conditions, muscular knee pain can feel “deep,” “inside the joint,” or “like something is torn,” even when imaging is normal.

Why this matters clinically

Muscle referral can:

Reproduce sharp or pinpoint pain at the patella

Create joint-line ache that mimics meniscal involvement

Produce medial or lateral knee pain during directional changes

Cause posterior knee fullness or tightness mistaken for a cyst

Limit knee flexion or extension due to protective guarding

Cause symptoms that fluctuate more than true structural injuries

Dry needling helps differentiate these patterns. When knee symptoms change quickly after releasing specific trigger points, like the quads, adductors, hamstrings, or calf muscles, it strongly suggests a muscle-driven component rather than a primary joint injury.

This is why dry needling fits naturally within knee pain treatment: it reduces muscular overload, improves joint mechanics, and helps clarify whether the knee pain is primarily muscular, structural, or mixed.

Knee Pain Patterns & Associated Trigger Points

Front of knee pain (patellofemoral-type)

Medial knee pain

Lateral knee pain

Posterior knee pain

Deep posterior knee / popliteal pain

Pain above the knee (quadriceps referral)

Pain below the knee

Knee Pain Trigger Points

The muscles below are frequently involved when knee pain is driven by quadriceps, hamstring, adductor, or lower-leg trigger points. Each is listed once with a brief referral pattern to guide focused palpation and treatment planning.

Rectus Femoris

Referral: Front of knee, patellar margin, and anterior thigh; often aggravated by stairs, running, squatting, or repeated sit-to-stand.

Vastus Medialis

Referral: Medial patellar border and anteromedial knee; commonly linked to patellofemoral pain and “giving way” on stairs.

Vastus Lateralis

Referral: Lateral knee and outer patella; symptoms often increase with downhill running, deep squats, or prolonged sitting.

Vastus Intermedius

Referral: Deep anterior knee aching that can feel “behind the kneecap,” especially with repeated flexion or long-duration sitting.

Biceps Femoris

Referral: Posterolateral knee and posterior thigh; often flares with sprinting, bending, or downhill walking.

Semitendinosus

Referral: Posterior knee line and upper-calf tightness; symptoms often feel like a “tight band” at the back of the knee.

Semimembranosus

Referral: Deep posteromedial knee pain; can mimic meniscal or joint-line irritation during bending or twisting.

Adductor Longus & Brevis

Referral: Medial knee aching with a pull from groin to knee; common in directional-change sports, cutting, and sit-to-stand.

Gracilis

Referral: Pes anserine/medial knee region; often described as a “line of pain” along the inner knee with walking or running.

Sartorius

Referral: Front and medial knee pain around the pes anserine; aggravated by pivoting, crossing the legs, or quick direction changes.

Tensor Fasciae Latae (TFL)

Referral: Lateral knee banding and outer-knee ache; often blamed on the “IT band” in runners and walkers.

Gastrocnemius

Referral: Posterior knee pain with a vertical spread into the calf; frequently provoked by hills, speed work, or prolonged standing.

Soleus

Referral: Deep, diffuse posterior knee and lower-calf soreness; can feel like “tight calves” that limit comfortable stair descent.

Plantaris

Referral: Focal posterior-medial knee pain; can mimic a small Baker’s cyst or posterior meniscus irritation.

Tibialis Posterior

Referral: Medial lower leg and ankle with perceived strain toward the medial knee, especially in overpronation patterns.

Tibialis Anterior

Referral: Anterolateral shin discomfort with secondary pulling around the front of the knee when overused for dorsiflexion.

Peroneus Longus

Referral: Lateral lower leg with perceived pull toward the lateral knee; often irritated by cutting, uneven surfaces, or side-to-side work.

Peroneus Brevis

Referral: Focal lateral/posterolateral ankle and lower leg; may contribute to a sense of “weakness” or pulling near the lateral knee during push-off.

Links route to individual muscle pages for detailed exam cues and self-care guidance. For broader context on treatment flow and dosing, see the Dry Needling Guide and the Trigger Points Guide.

How Dry Needling Fits Knee Pain With Quadriceps, Hamstring, Adductor & Calf Drivers

Dry needling for knee pain is most relevant when symptoms consistently track with muscle-driven load: sharp pain on stair descent, pressure at the front of the knee after sitting, medial knee pulling during longer walks, or outer-knee tension that returns during running or hills.

In these scenarios, hyper-irritable trigger points in the quadriceps, adductors, hamstrings, TFL, gastrocnemius, soleus, plantaris, tibialis posterior, tibialis anterior, and peroneals can all refer pain directly into the knee.

These trigger points may amplify tension around the patellar margin, increase compressive forces during running, or limit knee flexion and extension by altering muscle balance. When overloaded, these muscles can mimic joint-line pain, patellofemoral irritation, or even posterior meniscal discomfort, even when imaging is normal.

Treatment uses a thin, solid filiform needle to release specific neuromuscular points identified during the exam. It’s common to feel a deep ache, a brief twitch, or a familiar line of pain that travels into the knee region, signs that the target is accurate.

Sessions begin with a modest dose and expand gradually based on sensitivity and post-visit response. By reducing excessive tension in the quadriceps, hamstrings, adductors, and calf complex, dry needling can lower mechanical load on the knee and make it easier to progress strengthening, gait work, and functional exercises.

For an overview of session flow and technique, see the Dry Needling Guide.

What to Expect in a Session (Comfort, Pacing, Soreness)

A session begins with a review of symptom onset, stair and squat tolerance, sitting/standing patterns, and training loads. The knee, hip, and ankle are assessed for mobility, strength, and reproduction of familiar pain. Palpation guides muscle selection and dosing.

Clients often feel a deep ache or brief twitch during needling; these sensations tend to settle quickly. Post-session soreness may feel workout-like and can last 24–72 hours. Light mobility and hydration help this resolve smoothly.

Relief Timeline & Visit Cadence

Early change: within 1–3 sessions, improvements in stair comfort, sitting tolerance, and general load tolerance

Short series: 4–6 visits for more sustained improvement

Chronic cases: long-standing patterns or layered muscular drivers may require 10+ visits or maintenance

A 3–5 session trial helps determine responsiveness. If symptoms don’t shift, the muscle sequence, dosing strategy, or loading plan is revised.

Dry Needling for Knee Pain Research

Systematic Review & Meta-Analysis: Dry Needling for Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome (2025)

A 2025 systematic review and meta-analysis of 10 trials (466 patients) found that dry needling significantly reduced pain intensity and improved physical function (Kujala scores) in people with patellofemoral pain syndrome, with the strongest benefits in the 1–3 month window after treatment. Pain reduction was especially notable when targeting quadriceps and gluteus medius trigger points and when three trigger points were needled in a session, supporting a focused, multi-point myofascial strategy.

For full effect sizes and protocol details, see this systematic review and meta-analysis of dry needling for patellofemoral pain syndrome.

Dry Needling Plus Stretching for Patellofemoral Pain: Randomized Clinical Trial (2025)

This single-blind randomized clinical trial allocated 36 patients with patellofemoral pain to either stretching exercises alone or stretching plus dry needling to calf muscle trigger points over two weeks. Both groups improved, but the dry needling group showed greater reductions in pain intensity, larger gains in Kujala scores, higher pain-pressure thresholds, and increased ankle dorsiflexion range of motion, with benefits maintained at two-week follow-up.

Protocol structure and outcome measures are detailed in this randomized trial of combined dry needling and stretching for patellofemoral pain.

Dry Needling Combined With Exercise for Knee Osteoarthritis: Randomized Clinical Trial (2024)

In this randomized clinical trial of 33 individuals with knee osteoarthritis, all participants completed a structured therapeutic exercise program, while one group additionally received three sessions of dry needling to the popliteus muscle over three weeks. The dry needling plus exercise group demonstrated greater improvements in pain, stiffness, functional scores, strength, and reductions in pain catastrophizing and kinesiophobia, with effects persisting at three-month follow-up compared to exercise alone.

Detailed methods and clinical implications are presented in this randomized trial of popliteus dry needling combined with exercise for knee osteoarthritis.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Does dry needling help knee pain?

Dry needling may help knee pain when a muscular component is present—especially when tight quadriceps, hamstrings, adductors, or calf muscles are referring pain directly to the knee. Many people notice improved stair tolerance, easier squatting, and reduced sitting-related discomfort when muscular tension is addressed.

Can dry needling help patellofemoral knee pain (runner’s knee)?

Yes. Patellofemoral pain often stems from overactive quadriceps (vastus lateralis, rectus femoris), TFL tension, or calf restrictions that alter knee tracking. Dry needling calms these over-recruited muscles and may reduce the pulling forces around the patella.

Does dry needling help medial knee pain?

Medial knee pain is commonly referred from the adductors (longus/brevis), gracilis, or sartorius—not just joint structures. When these muscles are tight or irritated, they can mimic joint-line or MCL-type pain. Dry needling may reduce these muscular drivers.

Can dry needling help IT band or lateral knee pain?

Often, yes. Lateral knee pain frequently comes from TFL, vastus lateralis, biceps femoris, or peroneal tension. Dry needling targets these muscles to decrease the pulling and compression forces that irritate the outer knee during running or downhill movement.

Does dry needling help posterior knee pain?

Posterior knee pain is commonly referred from the hamstrings (semitendinosus, semimembranosus, biceps femoris), gastrocnemius, or plantaris. These muscles can create a sensation of deep joint-line pain or “tightness.” Dry needling may reduce this tension and improve bending tolerance.

Can dry needling replace physical therapy or strengthening?

Dry needling may reduce pain and muscular tension, but long-term results usually come from combining needling with progressive loading. Improving quadriceps, hamstring, glute, and calf strength helps maintain gains and prevents recurrence.

How many dry needling sessions are needed for knee pain?

Most people notice early change within 1–3 sessions, with more lasting improvement over 4–6 sessions. Chronic or long-standing cases may require 10+ sessions or periodic maintenance.

Is dry needling safe around the knee?

Dry needling around the knee is performed using anatomy-guided depth control and careful site selection. Treatment focuses on muscular contributors and avoids joint spaces or sensitive structures.

Ready to Try Acupuncture & Dry Needling?

Whether you’re struggling with acute or chronic pain, acupuncture and dry needling may help restore mobility and reduce pain - quickly and safely.

📍 Conveniently located in New York City

🧠 Experts in trigger point therapy, acupuncture, and dry needling

Book your appointment today with the experts at Morningside Acupuncture, the top-rated acupuncture and dry needling clinic in New York City.

Let us help you move better, feel stronger, and live pain-free.

Additional Resources & Next Steps

Learn More: Visit our Blog for further insights into our treatment approach.

What to Expect: During your initial consultation, we perform a comprehensive evaluation to develop a personalized treatment plan.

Patient Stories: Read testimonials from patients who have experienced lasting relief.

Sources:

Heewa, R., Madreseh, E., Anaraki, N., Emami Razavi, S. Z., & Maghbouli, N. (2025). The effectiveness of dry needling in patellofemoral pain syndrome patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, 44, 756–769. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40954658/

Safavi, S. N., Abbasi, L., Meftahi, N., & Moradi Alamdarloo, R. (2025). The effect of combined dry needling and stretching exercises on pain and function in patients with patellofemoral pain: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, 44, 423–431. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40954611/

Agost-González, A., Escobio-Prieto, I., Barrios-Quinta, C. J., Cardero-Durán, M. de L. Á., Espejo-Antúnez, L., & Albornoz-Cabello, M. (2024). Analysis of dry needling combined with an exercise program in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(23), 7157. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39685617/

Disclaimer: This web site is intended for educational and informational purposes only. Reading this website does not constitute providing medical advice or any professional services. This information should not be used for diagnosing or treating any health issue or disease. Those seeking medical advice should consult with a licensed physician. Seek the advice of a medical doctor or other qualified health professional for any medical condition. If you think you have a medical emergency, call 911 or go to the emergency room. No acupuncturist-patient relationship is created by reading this website or using the information. Morningside Acupuncture PLLC and its employees and contributors do not make any express or implied representations with respect to the information on this site or its use.